A

2003 paper by Nigel Hughes reviewed all of the trilobite species

with

descriptions of ventral features, presenting a summary table

including

the data below. It indicated that the typical trilobite bore a

pair of

antennae, then 3 cephalic limbs, followed by trunk (thorax +

pygidium)

limbs of variable number, depending on the number of thoracic

and

pygidial segments. The typical limb consisted of 6 or 7

podomeres. Olenoides serratus

remains the only trilobite with antenniform posterior cerci

preserved. In 2017 Zeng et al provided an update on species

bearing ventral preservation, which is adapted here:

| Species |

Age |

Locality |

Cephalic

limbs |

Thoracic

limbs |

Pygidial

limbs |

Podomeres |

Source |

| Eoredlichia

internedius |

E. Cambrian |

Chengjiang |

3? |

n/a |

n/a |

?7 |

Shu et al 1995; Ramskold &

Edgecombe 1996 |

| Yunnanocephalus

yunnanensis |

E. Cambrian |

Chengjiang |

4? |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Shu et al 1995 |

| Hongshiyanaspis yiliangensis |

E. Cambrian |

Kunming |

4? |

|

|

7 |

Zeng et al 2017 |

| Olenellus getzi |

E. Cambrian |

Lancaster, PA |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Dunbar 1925 |

| Olenoides serratus |

M. Cambrian |

Burgess Shale |

3 |

7 |

<6 |

6 |

Whittington 1975, '80 |

| Kootenia burgessensis |

M. Cambrian |

Burgess Shale |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Walcott 1918; Raymond 1920 |

| Elrathina cordillerae |

M. Cambrian |

Burgess Shale |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Walcott 1912, '18; Raymond

1920 |

| Elrathia

permulta |

M. Cambrian |

Burgess Shale |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Walcott 1918; Raymond 1920 |

| Agnostus pisiformis |

L. Cambrian |

Orsten, Sweden |

3 |

2 |

3 |

7 |

Muller & Walossek 1987 |

| Placoparia cambriensis |

M. Ordovician |

S. Wales |

3/3.5 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Whittington 1993; Edgecombe

& Ramskold 1999 |

| Isotelus

latus |

L. Ordovician |

. |

n/a |

?8 |

n/a |

n/a |

Raymond 1920 |

| Isotelus maximus |

L. Ordovician |

. |

n/a |

?8 |

?16 |

n/a |

Raymond 1920 |

| Triarthrus eatoni |

L. Ordovician |

Beecher Trilobite Bed |

3/3.5 |

14 |

>10 |

6 |

Raymond 1920; Cisne 1973;

Whittington & Almond 1987; Edgecombe &

Ramskold 1999 |

| Cryptolithus

tesselatus |

M.-L. Ordovician |

. |

n/a |

?5 |

>10 |

?7 |

Raymond 1920; Stormer 1939 |

| Primaspis trentonensis |

M.-L. Ordovician |

. |

n/a |

?10 |

n/a |

n/a |

Raymond 1920; Ross 1979 |

| Primaspis

sp. |

L. Ordovician |

. |

n/a |

>8 |

n/a |

n/a |

Ross 1979 |

| Ceraurus

pleurexanthemus |

L. Ordovician |

Walcott-Rust |

4 |

?11 |

3 |

n/a |

Walcott 1918, '21; Raymond 1920;

Stormer 1939, '51 |

| Flexicalymene senaria |

L. Ordovician |

Walcott-Rust |

n/a |

?13 |

>2 |

n/a |

Walcott 1918, '21; Raymond 1920 |

| Chotecops ferdinandi |

E. Devonian |

Hunsruck |

3 |

11 |

>12 |

6 |

Sturmer & Bergstrom 1973;

Bruton & Haas 1999 |

| Asteropyge sp. |

E. Devonian |

Hunsruck |

3 |

?11 |

>?4 |

n/a |

Sturmer & Bergstrom 1973 |

| Rhenops cf.

anserinus |

E. Devonian |

Hunsruck |

3/3.5 |

11 |

>6 |

7 |

Bergstrom & Brassel 1984;

Bartels et al 1998; Edgecombe & Ramskold 1999 |

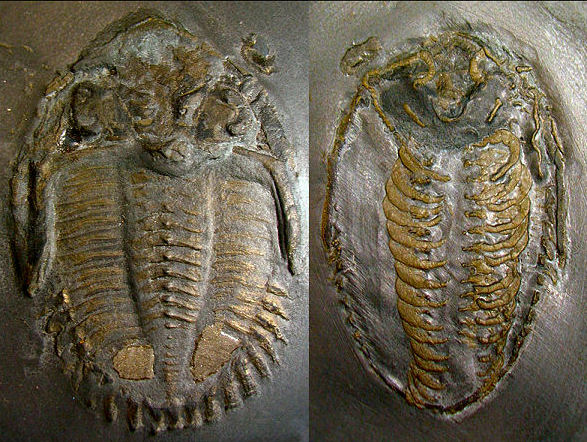

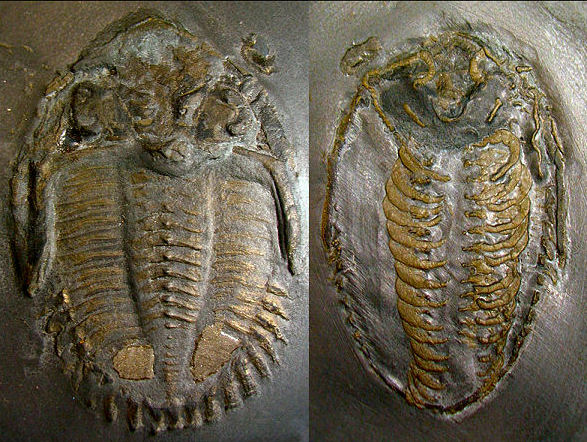

Here is an example specimen of Rhenops

cf. anserinus from Hunsruck, Germany, that has been

prepared to exposed both dorsal and ventral surfaces.

Limbs and antennae are preserved in pyrite.

Image courtesy of Andreas Ruckert:

At the 2008 Trilobite

Conference in Spain, this image of the New York trilobite

Triarthrus eatoni won

wide acclaim as the best preserved cephalic ventral features of

a

trilobite yet found. The arrangement of the cephalic limbs

converging

on the hypostome indicate how the gnathobases act as mouthparts

processing and manipulating food in the vicinity of the mouth,

which

underlies the hypostome. Image courtesy of the collection of Dr.

Ed

Staver:

Bartels, C., D.E.G. Briggs, and G. Brassel. 1998. The

Fossils of the Hunsruck slate: Marine life in the Devonian.

Cambridge Paleontological Series Number 3. Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge.

Bergstrom, J. & G. Brassel 1984. Legs in the trilobite Rhenops

from the lower Devonian Hunsruck Shale. Lethaia

17:67-72.

Bruton, D.L. & W. Haas 1999. The anatomy and functional

morphology of Phacops

(Trilobita) from the Hunsruck Slate (Devonian). Palaeontographica

Abteilung A 253:1-75.

Cisne, J.L. 1973. Life history of an Ordovician trilobite Triarthrus

eatoni. Ecology

54:135-42.

Dunbar, C.O. 1925. Antennae in Olenellus

getzi, n. sp. Amer.

J. of Science. Series 5. 9:303-8.

Edgecombe, G.D. & L. Ramskold 1999. Relationships of

Cambrian Arachnata and the systematic position of Trilobita.

J. Paleontol. 73:263-87.

Hughes, N.C. 2003. Trilobite tagmosis and body patterning from

morphological and developmental perspectives. Integr.

Comp. Biol. 43:185

Muller, K.J. & D. Wallossek 1987. Morphology, ontogeny, and

life habit of Agnostus

pisiformis from the Upper Cambrian of Sweden. Fossils

and Strata 19:1-124.

Ramskold L. & G.D. Edgecombe 1996. Trilobite appendage

structure -- Eoredlichia

reconsidered. Alcheringa 20:269-76.

Raymond P.E.1920. The appendages, anatomy, and relationships of

trilobites. Memoirs of

the Connecticut Academy of Sciences 7:1-169.

Ross, R.J. Jr. 1979. Additional trilobites from the Ordovician

of Kentucky. United States

Geological Survey Professional Paper 1066-D:1-13.

Shu, D., G. Geyer, L. Chen, and X. Zhang. 1995. Redlichiacean

trilobites with preserved soft-parts from the lower Cambrian

Chengjiang

fauna (South China). Berlingeria,

Special Issue 2:203-41.

Stormer, L. 1939. Studies on trilobite morphology, Part I. The

thoracic appendages and their phylogenetic significanceNorsk.

Geol. Tidssk. 19:143-274.

Stormer, L. 1951. Studies on trilobite morphology, Part III.

The ventral cephalic sutures, with remarks on the zoological

position

of the trilobites. Norsk.

Geol. Tidssk. 29:108-58.

Stürmer, W. & Bergström, J. 1973: New

discoveries on trilobites by X-rays. Paläontologische

Zeitschrift

47, 104–141.

Walcott, C.D.1912. Cambrian geology and paleontology II. No. 6.

Middle

Cambrian Branchiopoda, Malacostraca, Trilobita, and

Merostomata. Smithsonian

Miscellaneous Collections 57:145-228.

Walcott, C.D. 1918. Cambrian geology and paleontology IV. No.

4. Appendages of trilobites. Smithsonian

Miscellaneous Collections 67:115-216.

Walcott, C.D.1921. Cambrian geology and paleontology IV. Notes

on structure of Neolenus.

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 67:365-456.

Whittington, H.B. 1975. Trilobites with appendages from the

Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale, British Columbia. Fossils

and Strata 4:97-136.

Whittington, H.B. 1980. Exoskeleton, moult stage, appendage

morphology, and habits of the Middle Cambrian trilobite Olenoides

serratus. palaeontology 23:171-204.

Whittington, H.B. 1993. Anatomy of the Ordovician trilobite

Placoparia. Phil. Trans. R.

Soc. London. series B 339:109-18.

Whittington, H.B. & J.E. Almond 1987. Appendages and habits

of the Upper Ordovician trilobite Triarthrus

eatoni. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London. series B 317:1-46.

Zeng, H., F. Zhao, Z. Yin, and M. Zhu. 2017. Appendages of an

Early Cambrian metadoxidid trilobite from Yunnan, SW China

support mandibulate affinities of trilobites and artiopods. Geol.

Mag. 154(6):1306-28.

|

Unlike the thicker dorsal shell of a trilobite, many of the

ventral (underside) features, including limbs and antennae,

usually are not preserved. The

ventral portions that are

typically preserved include the doublure

(a ventral extension of the dorsal exoskeleton), a special part

of the doublure, typically separated by sutures at the anterior

of the cephalon, called the rostral

plate, and a hard mouthpart called the hypostome,

that typically underlies the glabella.

Unlike the thicker dorsal shell of a trilobite, many of the

ventral (underside) features, including limbs and antennae,

usually are not preserved. The

ventral portions that are

typically preserved include the doublure

(a ventral extension of the dorsal exoskeleton), a special part

of the doublure, typically separated by sutures at the anterior

of the cephalon, called the rostral

plate, and a hard mouthpart called the hypostome,

that typically underlies the glabella.