Eyes and systematics: The schizochroal eyes of phacopids have attracted research for over 150 years, and the arrangement and number of lenses in the holaspid eye has been subject to analyses exploring their utility in distinguishing between populations, species, and higher taxa, as well as the amount of variation that might be found within populations. Indeed, there are studies that have demonstrated that there can be differences between the number and arrangement of lenses between the two eyes on a single specimen!

It was pioneers such as Steininger (1831) and Clarke (1889) that first diagrammed the arrangement of lenses and suggested that these might be useful in classification, but Clarkson (1966) who established the system of charting and counting dorso-ventral files (DVF) of lenses. The classic study of Niles Eldredge (1972) used DVF among other characters to distinguish the species and subspecies in North American

Phacops rana and

P. iowensis. He pointed out that

P. iowensis invariably bore 13 dorso-ventral files, while

P. rana, depending on subspecies, ranged from 15-18 DVF, with the most primitive subspecies,

Phacops rana rana, bearing the largest number of files. He concluded that P. rana and P. iowensis were only distantly related, a conclusion also reached by Struve (1990), who erected genus

Eldredgeops and placed

P. rana (but not

P. iowensis) within it.

Similarly, Campbell (1977) noted differences in the number and arrangement of lenses in the eyes of what he then called "large-eyed" and "small-eyed" morphs of

Paciphacops raymondi from the Haragan formation in Oklahoma. Later, Ramsköld and Werdelin (1991) revised that complex, recognizing not only separate species, but assigning them to two different genera:

Paciphacops campbelli, with eyes bearing DVF of only 3-4 lenses/file for the "smalled-eyed" morph, and

Kainops raymondi, with 6-7 lenses per file for the "large-eyed" morph.

Citations for Eyes and Systematics section: Clarke, J.M. 1889. The structure and development of the visual area in the trilobite,

Phacops rana, Green.

J. Morphol. 2:253-70

Thomas, A.T. 2005. Developmental palaeobiology of trilobite eyes and its evolutionary significance.

Earth-Science Reviews 71:77–93.

Eldredge, N. 1973. Systematics of Lower and Lower Middle Devonian species of the trilobite

Phacops Emmrich in North America.

Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 151:285-338.

Eldredge, N. 1972. Systematics and evolution of

Phacops rana (Green, 1832) and

Phacops iowensis Delo, 1935 (Trilobita) for the Middle Devonian of North America.

Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 147:45-114.

Steininger, J. 1831. Observations sur les fossiles du calcaire intermediaire de l'Eifel.

Mem. Soc. Geol. France 1(15):331-71.

Struve, W. 1990. [Paläozoologie III (1986-1990)].

Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 127: 251-279.

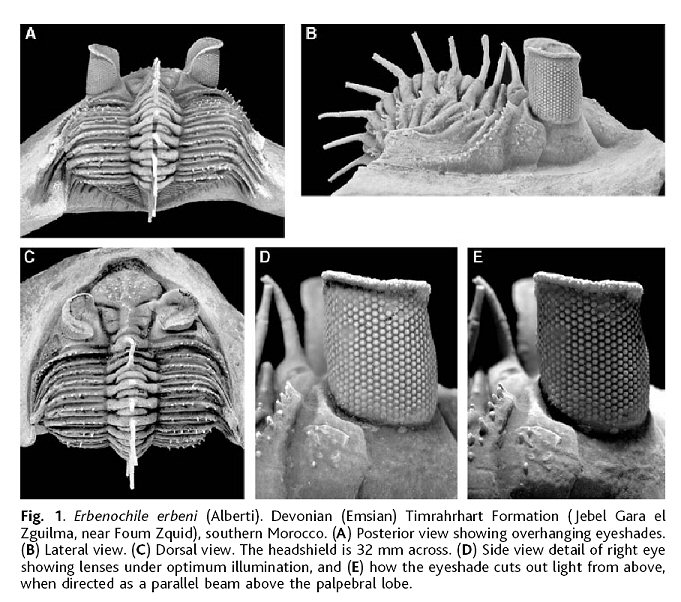

SEM

images of the trilobite schizochroal eye courtesy of Dr. Riccardo Levi-Setti from his superb book "Trilobites"

All early trilobites (Cambrian), had holochroal eyes and it would seem hard to evolve the distinctive phacopid schizochroal eye from this form. The answer is thought to lie in ontogenetic (developmental) processes on an evolutionary time scale. Paedomorphosis is the retention of ancestral juvenile characteristics into adulthood in the descendent. Paedomorphosis can occur three ways: Progenesis (early sexual maturation in an otherwise juvenile body), Neoteny (reduced rate of morphological development), and Post-displacement (delayed growth of certain structures relative to others). The development of schizochroal eyes in phacopid trilobites is a good example of post-displacement paedomorphosis. The eyes of immature holochroal Cambrian trilobites were basically miniature schizochroal eyes. In Phacopida, these were retained, via delayed growth of these immature structures (post-displacement), into the adult form.

All early trilobites (Cambrian), had holochroal eyes and it would seem hard to evolve the distinctive phacopid schizochroal eye from this form. The answer is thought to lie in ontogenetic (developmental) processes on an evolutionary time scale. Paedomorphosis is the retention of ancestral juvenile characteristics into adulthood in the descendent. Paedomorphosis can occur three ways: Progenesis (early sexual maturation in an otherwise juvenile body), Neoteny (reduced rate of morphological development), and Post-displacement (delayed growth of certain structures relative to others). The development of schizochroal eyes in phacopid trilobites is a good example of post-displacement paedomorphosis. The eyes of immature holochroal Cambrian trilobites were basically miniature schizochroal eyes. In Phacopida, these were retained, via delayed growth of these immature structures (post-displacement), into the adult form.