A dark reconstruction of Anomalocaris canadensis

cruising above the ocean floor captures the essence of the sleek, swimming

hunter. The eyestalks are swiveled forward, checking the floor ahead for

prey

A dark reconstruction of Anomalocaris canadensis

cruising above the ocean floor captures the essence of the sleek, swimming

hunter. The eyestalks are swiveled forward, checking the floor ahead for

prey

|

The combination of physical model photographed against

a real marine setting is effective here. The reconstruction depicts the swimming

lobes as dorsal features, which does not match the fossil evidence. Neither

does the strong overlap between the last swimming lobes and the fantail.

|

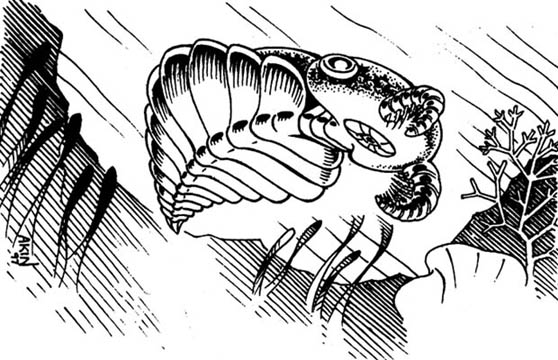

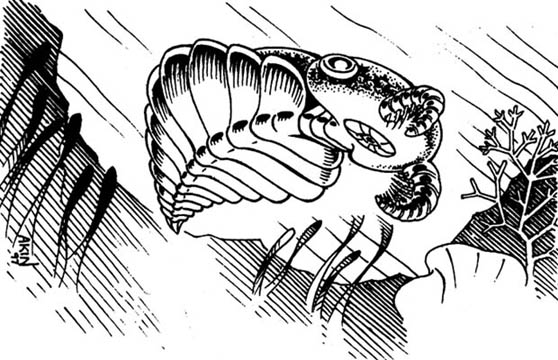

This pen and ink rendition of Laggania cambria does

justice to the fossil specimens by showing ventral swimming lobe placement.

The sweep of the curve of the body is quite attractive, as is the tilted orientation

of the scene. Although the depiction of a distinct "head" matches that of

Whittington and Briggs (1985), the fossils specimens of Laggania really don't

show such a strong separation.

This pen and ink rendition of Laggania cambria does

justice to the fossil specimens by showing ventral swimming lobe placement.

The sweep of the curve of the body is quite attractive, as is the tilted orientation

of the scene. Although the depiction of a distinct "head" matches that of

Whittington and Briggs (1985), the fossils specimens of Laggania really don't

show such a strong separation.

|

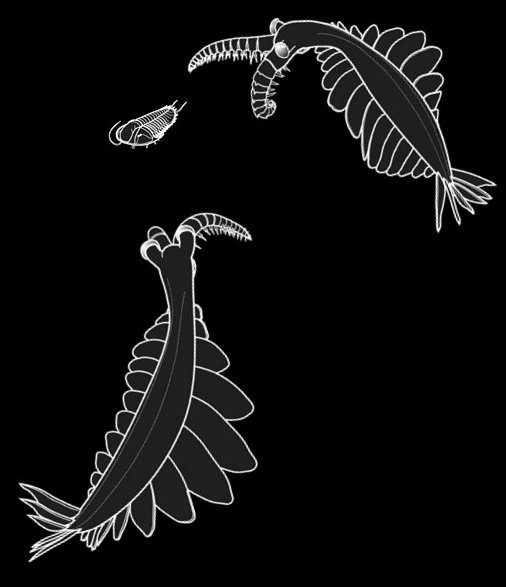

This rendition of Laggania cambria as a fast-moving

swimmer shows a dorsoventrally flattened animal that is streamlined for swimming.

The sine-wave of swimming movements along the lateral lobes is clearly shown.

The animal almost has a squid-like demeanor.

|

This small image of Anomalocaris chomping on a trilobite

depicts the swimming lobes as independent, wing-like flaps, each capable of

movment.

This small image of Anomalocaris chomping on a trilobite

depicts the swimming lobes as independent, wing-like flaps, each capable of

movment.

The same model as the image above, but in a larger, swimming

depiction, suggests that there was dorsal segmentation, which is possible,

not clearly shown in fossil specimens. The imbrication of the tail lobes seems

correct, and the angled depiction effectively avoids the problem of whether

the fantail overlapped with the segments bearing the last pairs of swimming

lobes.

The same model as the image above, but in a larger, swimming

depiction, suggests that there was dorsal segmentation, which is possible,

not clearly shown in fossil specimens. The imbrication of the tail lobes seems

correct, and the angled depiction effectively avoids the problem of whether

the fantail overlapped with the segments bearing the last pairs of swimming

lobes.

|

This image, as if taken hovering just above the surface

of the Cambrian ocean, shows a red-eyed Anomalocaris cruising just below

the surface. Once againm dorsal segmentation is apparent, and the artist

chose to depict the dorsal fantail as independent of the swimming lobes.

|

Sometimes the artistic renditions get quite imaginative

and bright. This anomalocarid is not a match for any known species, but Laggania

is probably the inspiring taxon. The fins are dorsally placed, which is a

problem, but I like the fluorescent mouth, and the bright color patterns.

Sometimes the artistic renditions get quite imaginative

and bright. This anomalocarid is not a match for any known species, but Laggania

is probably the inspiring taxon. The fins are dorsally placed, which is a

problem, but I like the fluorescent mouth, and the bright color patterns.

|

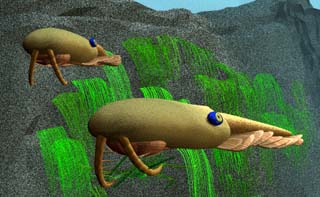

A pair of Laggania cruise the Burgess cliffs in this

depiction: a good match for the Whittington & Briggs 1985 reconstruction.

One of the reasons Laggania is popular with computer artists is that

the different body parts can be constructed readily using simple, geometric

"primitives" (basic shapes without much complex topology), then combined

and posed at will.

A pair of Laggania cruise the Burgess cliffs in this

depiction: a good match for the Whittington & Briggs 1985 reconstruction.

One of the reasons Laggania is popular with computer artists is that

the different body parts can be constructed readily using simple, geometric

"primitives" (basic shapes without much complex topology), then combined

and posed at will.

|

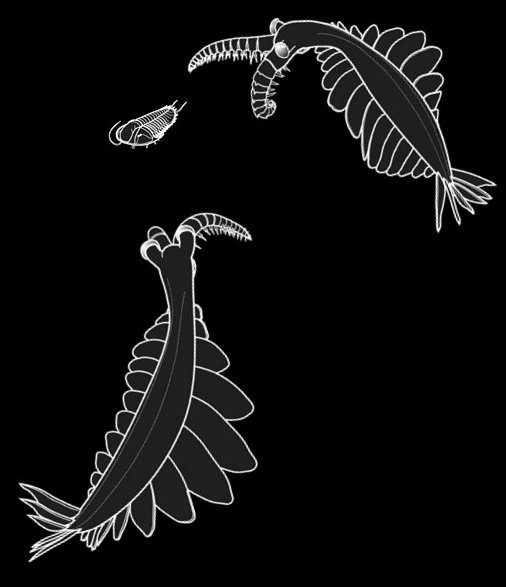

My rendition of Anomalocaris canadensis,

created in Macromedia Freehand, captures a concept of the animal as an active

and acrobatic swimmer, able to capture evasive swimming prey. The swimming

lobes are ventral, and the dorsal fantail follows the last pa

My rendition of Anomalocaris canadensis,

created in Macromedia Freehand, captures a concept of the animal as an active

and acrobatic swimmer, able to capture evasive swimming prey. The swimming

lobes are ventral, and the dorsal fantail follows the last pa

ir of swimming lobes.

|

In contrast, I depict Laggania

as a sweep-feeding planktivore, that moves through the well-lit upper waters,

raking in small swimming creatures, much as manta rays and whale-sharks do

today. In ecological thought, the partitioning of trophic guilds by two species

of anomalocarids in this manner would allow for their coexistence without

much competition.

|

|

I end this page with an image I created of two Anomalocaris

canadensis converging on an Olenoides trilobite. This doesn't

necessarily imply that they engaged in cooperative hunting. The second Anomalocaris

could have merely been attracted to the commotion caused by the activities

of the other. It would be interesting to consider what kinds of agonistic

behaviors occurred between individuals, and whether they engaged in any specialized

territorial or courtship behaviors.

|